A Branded House architecture centers around a strong parent brand (corporate name and brand identity) that is prominently displayed on all products.

This is a common approach for new breweries—by uniting all products under a single parent brand, products can make a bigger impact at launch. Through repetition and consistency, this approach lends a feeling of reliability over time (and tends to hold together better on shelf at retail.)

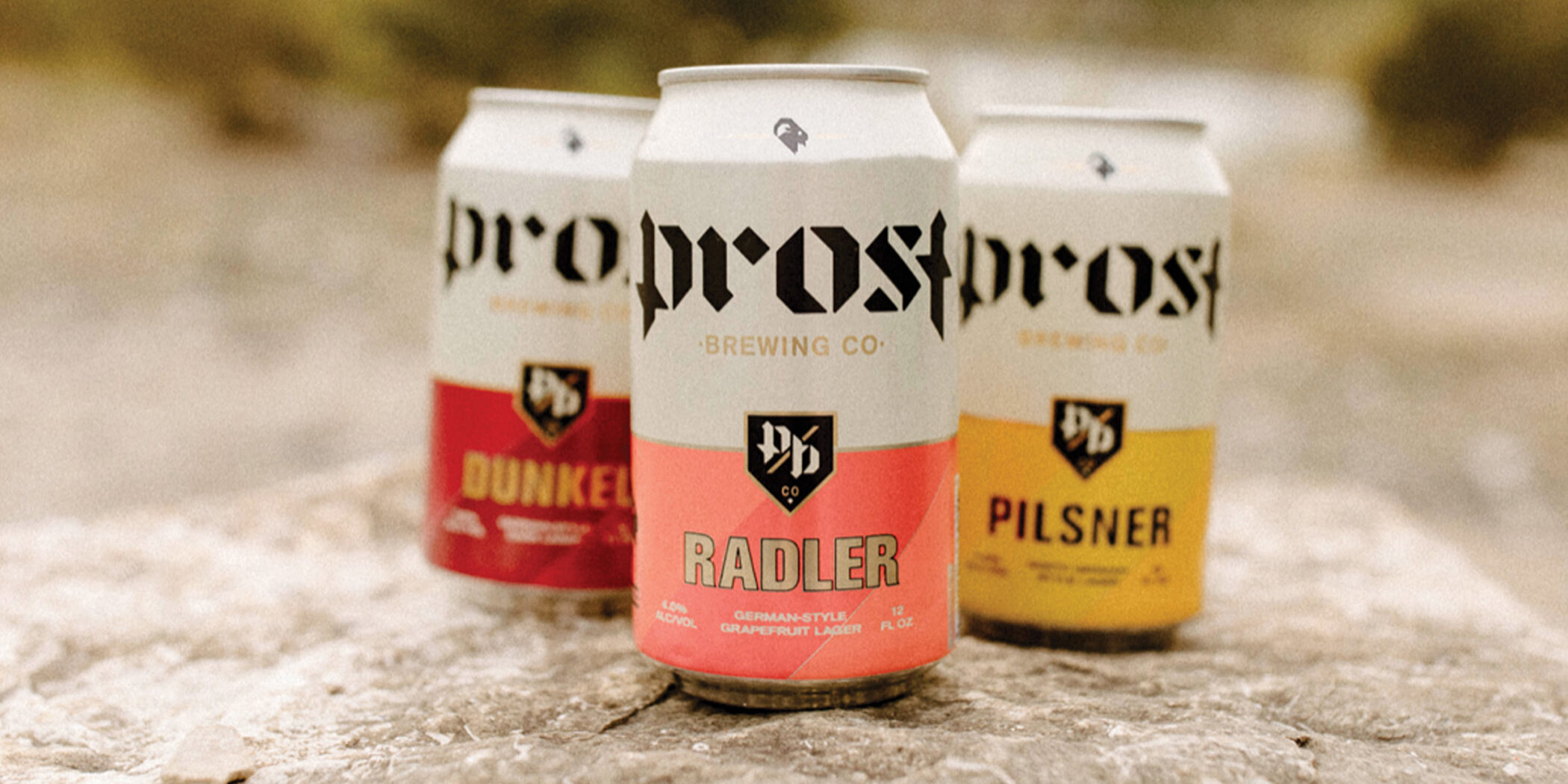

A Branded House creates a consistent experience across all your brands and touch points, building equity and recognition for the parent brand every step of the way. Visually, this manifests in the consistent and intentional use of logos, icons, typography, color and packaging composition.

Under this approach, your parent brand is the main purchasing driver (the reason someone is buying your product) for customers.

WHEN A BRANDED HOUSE MAKES SENSE

- When you’re a new brewery looking to build and grow your reputation through clarity and repetition

- When you’re an existing brewery with too many disparate offerings that have become unwieldy to manage.

- When you’re producing higher volume products where consistency and shelf presence at retail are key.

- When your brewery team has limited internal capacity and needs an efficient way to generate labels on a tight timeline.

- When you have high levels of brand equity and this new product aligns with your brand as it currently stands.

Some Advantages

A Branded House allows for economies of scale.

When you are focusing your efforts into a single message, you can put all of your time and promotional dollars behind that single brand. Every packaging decision you make, every event you host, every community partnership you make all help to develop the parent brand’s reputation and solidify your positioning. This makes it the most cost-effective operating expense (OpEx) model available.

A Branded House brings clarity to a wide array of offerings.

Why do I need to buy this? Why should I trust it? Customers ask themselves these questions (in a matter of microseconds) at every visit to the retail shelf. A Branded House allows you to present a unified front by credit of your reputation. If customers know and trust your brewery, then they don’t need to keep tabs on every single SKU you produce. Instead, they scan for your name as a quick signal that the product in front of them, whether beer or beyond, is worth the spend.

A Branded House allows for efficiency and clarity when rolling out new products.

From an internal process standpoint, rolling out new products is easier under a monolithic Branded House because you’re never starting from scratch. Your messaging is already defined and customers know what to expect. You may already have a package design template set up, or at least know the cues that need to be present in order to carry the message of the parent brand. This can be a boon for tight timelines, and even allow efficiencies such as ordering printed cans (and other prepared goods) before more specific product decisions are finalized.

Caveats

If one touch point falters, the entire brand can be affected.

Keep in mind that a Branded House approach can be a double-edged sword. If you release a new product that is a total whiff, your (more or less) identically-designed existing brands could take a negative hit simply by association. If an unrelated crisis damages your customers’ perception of your brand, your entire portfolio can suffer. Fair or unfair, this is an important consideration to keep in mind with this strategy.

Your parent brand may not be adequately suited for all opportunities out of the box.

Over time, your parent brand will come to stand for a few very specific ideas and promises. You continue to reinforce and defend this positioning with each new product you release and via the rapport you build with your customers. These promises and values might not be suited to a planned extension.

Can a renowned lager brewery make a canned cocktail? Can a lauded IPA brewery wade into the seltzer category without taking a bunch of flack online? Credibility and coherence are at risk when a parent brand swerves too far outside of its own lane.

There is a risk of “image fatigue” over the long term.

The explosion of craft breweries in the United States has inundated consumers with a non-stop litany of shiny new beers. As a result, the timeline for what is considered “new” and “fresh” in a customer’s mind has tightened dramatically. Depending on your specific market, there is a chance that the repetition of a templated, monolithic approach to branding and package design can seem rote and lose its impact on the shelf over time.